Sunday, 27 January 2013

Jimmy Savile Helped by Failing British Legal System to Escape Justice

How my father may have helped Jimmy Savile escape justice

The son of George Carman

QC recalls how his father helped paedophiles escape justice

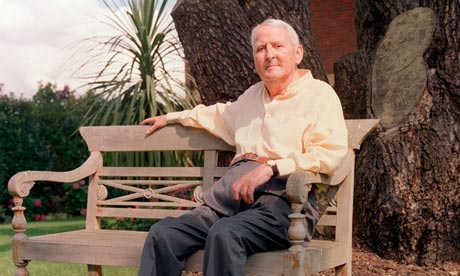

George Carman QC. Photograph: Eamonn

Mccabe

For years the Duncroft girls have been

trying to get justice. The Police would do nothing about Jimmy Savile because he

had them in his pocket, the Press did try to help but the British Injustice

System worked against them. Read what the son of Lord Carman QC had to

say:-

Roy Greenslade's blog last Wednesday reported that

Paul Connew, when editor of the Sunday Mirror in

1994, did have "credible and convincing" evidence from two women who claimed

that Jimmy Savile had been

guilty of abusing them at a children's home. Though "totally and utterly

convinced" they were telling the truth, the paper's lawyers, after a careful

assessment, decided it wasn't strong enough to risk publication. The risk was

libel and the substantial costs and damages that the newspaper could face should

they lose a subsequent high court case from the litigious Savile. To the

in-house lawyers at Mirror Group, the risk seemed too great. Connew went further

in talking about his guilt relating to this on Newsnight last Thursday.

But there is perhaps another angle to the story.

In 1992, my father, George Carman QC, had been retained by Savile's lawyers over a different matter, which never reached court. By 1994, the name Carman, and what he could do in cross-examination, put such fear into the minds of litigants, lawyers and editors that libel cases were settled and, in some circumstances, perhaps stories were not published. Savile may have been one of those. As an indication of Carman's universal demand, and the respect he instilled, one has to look no further than the Guardian itself. In 1995, the editor, Alan Rusbridger, when faced with a libel action from Jonathan Aitken said: "We'd better get Carman – before Aitken gets him." They did and Aitken lost.

My father's relationship with Mirror Group Newspapers, publishers of the Sunday Mirror, is worth examining. Up to a week before his death in December 1991, he had been advising Robert Maxwell about a libel case against the BBC relating to a Panorama exposé. Ensconced with him for many hours in his chambers, and on the top floor of the old Mirror Group building, the two men discussed revenge on the Beeb. It never happened: the case went with Maxwell to the grave. Six weeks later, Robert's son, Kevin, was hauled before Parliament's social security committee to discuss the missing millions from the Mirror Group pension fund. He said nothing, leaving my father to deliver a two-hour televised homily on his behalf, concerning his client's right to silence.

Carman went on to act successfully for Mirror Group in several libel cases, saving them a substantial sum in costs and damages. But in October 1993, he changed sides, as lawyers sometimes do, under what is called the cab rank principle: first come, first served. He was retained by Elton John in a libel case against the Sunday Mirror over false allegations that he suffered from a bizarre eating disorder that caused him to spit out the food he was eating. In court, Carman went for the jugular, demanding punitive damages from the jury for publishing an untrue story, inviting them "to wipe the smile off the faces of the board of directors of Mirror Group Newspapers".

The jury did exactly that, awarding £75,000 for the libel and £275,000 in punitive damages. It added to the £1m in damages which Elton had got from the Sun five years earlier over allegations concerning his private life. Colin Myler, then editor of the Sunday Mirror, and later the last ever editor of the News of the World, labelled the damages "excessive", adding: "When you consider that a person who loses an eye receives in the region of £20,000 compensation, it helps to put this case into perspective."

Connew was appointed as Myler's successor in 1994. The Savile story landed in his lap shortly afterwards. For the in-house lawyers at Mirror Group, the prospect of a Carman cross-examination of the two women, who would be their key witnesses, may have influenced their thinking. If he had achieved £350,000 for Elton, how astronomic might the damages have been had Savile won, when the libel was potentially much greater? Perhaps the risk of publishing the story was considered too great because of George Carman.

They also might have had another Carman performance in mind: his successful defence of the late Peter Adamson, better known as Len Fairclough in Coronation Street. In 1983, Adamson was tried for indecently assaulting two eight-year-old girls in a public swimming pool, in Haslingden. Following complaints of previous incidents, the assaults had been witnessed by two police officers watching through a porthole, which gave an underwater view of the pool. In cross-examining the officers and the girls, my father destroyed the case. Adamson walked free. The following year, he told a Sun reporter: "I am totally guilty of everything the police said." When the Sun reported the story, no further action was taken. Adamson died in 2002.

Like Savile, he never paid for his crimes. souce http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/oct/14/dominic-carman-jimmy-savile-and-my-father

What are the wider implications of this sorry tale? It means that the UK does not have a functioning justice system. The best liar wins in Court. Poor people have no chance at all. Criminals go free and the innocent are convicted. This all leads to Justice Denied.

In 1992, my father, George Carman QC, had been retained by Savile's lawyers over a different matter, which never reached court. By 1994, the name Carman, and what he could do in cross-examination, put such fear into the minds of litigants, lawyers and editors that libel cases were settled and, in some circumstances, perhaps stories were not published. Savile may have been one of those. As an indication of Carman's universal demand, and the respect he instilled, one has to look no further than the Guardian itself. In 1995, the editor, Alan Rusbridger, when faced with a libel action from Jonathan Aitken said: "We'd better get Carman – before Aitken gets him." They did and Aitken lost.

My father's relationship with Mirror Group Newspapers, publishers of the Sunday Mirror, is worth examining. Up to a week before his death in December 1991, he had been advising Robert Maxwell about a libel case against the BBC relating to a Panorama exposé. Ensconced with him for many hours in his chambers, and on the top floor of the old Mirror Group building, the two men discussed revenge on the Beeb. It never happened: the case went with Maxwell to the grave. Six weeks later, Robert's son, Kevin, was hauled before Parliament's social security committee to discuss the missing millions from the Mirror Group pension fund. He said nothing, leaving my father to deliver a two-hour televised homily on his behalf, concerning his client's right to silence.

Carman went on to act successfully for Mirror Group in several libel cases, saving them a substantial sum in costs and damages. But in October 1993, he changed sides, as lawyers sometimes do, under what is called the cab rank principle: first come, first served. He was retained by Elton John in a libel case against the Sunday Mirror over false allegations that he suffered from a bizarre eating disorder that caused him to spit out the food he was eating. In court, Carman went for the jugular, demanding punitive damages from the jury for publishing an untrue story, inviting them "to wipe the smile off the faces of the board of directors of Mirror Group Newspapers".

The jury did exactly that, awarding £75,000 for the libel and £275,000 in punitive damages. It added to the £1m in damages which Elton had got from the Sun five years earlier over allegations concerning his private life. Colin Myler, then editor of the Sunday Mirror, and later the last ever editor of the News of the World, labelled the damages "excessive", adding: "When you consider that a person who loses an eye receives in the region of £20,000 compensation, it helps to put this case into perspective."

Connew was appointed as Myler's successor in 1994. The Savile story landed in his lap shortly afterwards. For the in-house lawyers at Mirror Group, the prospect of a Carman cross-examination of the two women, who would be their key witnesses, may have influenced their thinking. If he had achieved £350,000 for Elton, how astronomic might the damages have been had Savile won, when the libel was potentially much greater? Perhaps the risk of publishing the story was considered too great because of George Carman.

They also might have had another Carman performance in mind: his successful defence of the late Peter Adamson, better known as Len Fairclough in Coronation Street. In 1983, Adamson was tried for indecently assaulting two eight-year-old girls in a public swimming pool, in Haslingden. Following complaints of previous incidents, the assaults had been witnessed by two police officers watching through a porthole, which gave an underwater view of the pool. In cross-examining the officers and the girls, my father destroyed the case. Adamson walked free. The following year, he told a Sun reporter: "I am totally guilty of everything the police said." When the Sun reported the story, no further action was taken. Adamson died in 2002.

Like Savile, he never paid for his crimes. souce http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/oct/14/dominic-carman-jimmy-savile-and-my-father

What are the wider implications of this sorry tale? It means that the UK does not have a functioning justice system. The best liar wins in Court. Poor people have no chance at all. Criminals go free and the innocent are convicted. This all leads to Justice Denied.

![europe_italy_valcamonica_[10000BCE]](http://i1.wp.com/vigilantcitizen.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/europe_italy_valcamonica_10000BCE.gif?zoom=1.5&resize=462%2C325)