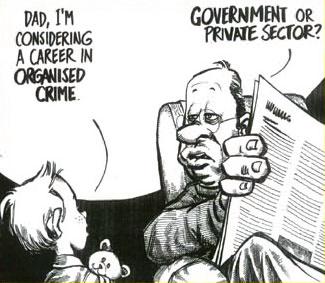

The Criminal State

Gerard N. Casey | LewRockwell.com

Excerpted from Libertarian Anarchy: Against the State (2012). 454 views

December 15, 2012

Excerpted from Libertarian Anarchy: Against the State (2012). 454 views

December 15, 2012

I intend this statement to be understood literally and not as some form of rhetorical exaggeration. The argument is simple. Theft, robbery, kidnapping and murder are all crimes. Those who engage in such activities, whether on their own behalf or on behalf of others are, by definition, criminals. In taxing the people of a country, the state engages in an activity that is morally equivalent to theft or robbery; in putting some people in prison, especially those who are convicted of so-called ‘victimless crimes’ or when it drafts people into the armed services, the state is guilty of kidnapping or false imprisonment; in engaging in wars that are other than purely defensive or, even if defensive, when the means of defence employed are disproportionate and indiscriminate, the state is guilty of manslaughter or murder.

I intend this statement to be understood literally and not as some form of rhetorical exaggeration. The argument is simple. Theft, robbery, kidnapping and murder are all crimes. Those who engage in such activities, whether on their own behalf or on behalf of others are, by definition, criminals. In taxing the people of a country, the state engages in an activity that is morally equivalent to theft or robbery; in putting some people in prison, especially those who are convicted of so-called ‘victimless crimes’ or when it drafts people into the armed services, the state is guilty of kidnapping or false imprisonment; in engaging in wars that are other than purely defensive or, even if defensive, when the means of defence employed are disproportionate and indiscriminate, the state is guilty of manslaughter or murder.For many people, perhaps most, these contentions will seem both shocking and absurd. Some will immediately object that taxation is clearly not theft. They may say, as Craig Duncan does [1] , that since you don’t have legal title to all your pre-tax income the state commits no crime in appropriating that part of your income to which it is entitled. The problem with this objection is that it completely begs the question – is the state entitled to part of your income?

The libertarian contention that taxation is the moral equivalent of theft can be true, Duncan believes, only if people have a moral right ‘to keep and control all their earnings’ [2] but this claim, he thinks, is beset with fatal problems. To illustrate this point, he rehearses the tragedy of Annie, the antiques dealer, who has to hand over 20 per cent of her earnings to the owner of the premises she rents to conduct her business. If Annie were to claim that she had a right to all her earnings and shouldn’t be obliged to fork over the 20 per cent, the building owner will respond that without his premises, she wouldn’t have been able to make any sales in the first place. ‘Something similar,’ says Duncan, ‘is true of government taxes.’ [3] If it weren’t for the state’s enforcing contracts, protecting property rights, keeping the peace, printing currency, preventing monopolies, and so on, you or anyone else wouldn’t be able to go about your daily business. So, the argument goes, by analogy the state has a moral entitlement to a portion of your earnings, presumably to at least an amount sufficient to cover the costs of these services.

This analogy is so weak it not only limps, as most analogies do, but it positively staggers around on one leg. First of all, Annie presumably has made an agreement with her landlord and did so freely. If she doesn’t want to hand over 20 per cent of her earnings to him, she can try to renegotiate the contract or take her business elsewhere. In stark contrast, the average citizen has made no agreement with the state. The state unilaterally determines the amount that citizens must ‘pay’. Citizens are not at liberty to take their ‘business’ elsewhere since the state forcibly excludes competitors who might be willing to supply more cheaply the services provided by the state. Duncan’s analogy, if it has any force at all, has it only if it runs in the opposite direction. On the libertarian way of thinking about it, taking commercial relations as the norm, Annie Citizen is forced to do her business in premises of her landlord’s (the state’s) choosing, paying whatever rent he (the state) determines he deserves, and her landlord (the state) can legitimately use violence to prevent someone else offering her a better deal.

Some will reject the charge of false imprisonment or kidnapping that I lay against the state. People are put in gaol, they will say, only if they are convicted of committing a crime; the fact that they’re in gaol means they’re criminals. The state is not only not doing anything wrong in putting them there, it’s doing something positively good by protecting us from these miscreants. This objection, of course, draws our attention firmly to the question of which courses of conduct actually constitute crime. While most people will agree that murder, robbery, kidnapping and assault are crimes, involving, as they do, gross interference with the lives, liberties and properties of others, it’s not entirely clear just what awful deed is being done by Tom, Dick and Harriet when, for example, they smoke pot in the privacy of their rooms and why it should require violent intervention by the state to prevent it.

Through taxation, the state aggresses against the property of the individual, and through the variety of compulsory monopolies it enjoys, the state aggresses against the free exchange of goods and services in the area of which it claims control. Murray Rothbard writes that ‘the State, which subsists on taxation, is a vast criminal organization, far more formidable and successful than any “private” Mafia in history.’ He makes the obvious point that ‘it should be considered criminal…according to the common apprehension of mankind, which always considers theft to be a crime’. [4] As the satirist, H. L. Mencken, notes, ‘The intelligent man, when he pays taxes, certainly does not believe that he is making a prudent and productive investment of his money; on the contrary, he feels that he is being mulcted in an excessive amount for services that, in the main, are useless to him, and that, in substantial part, are downright inimical to him.’ [5]

Unless you work for the state, your direct encounters with it are likely to be unpleasant. Think of being manhandled at an airport and made to feel as if you were a criminal but not wanting to protest in case the securicrats deem you a security threat and detain you. If you’ve ever had to deal with the state’s bureaucrats in, let’s say, an immigration department, you’ll have firsthand experience of what Shakespeare calls ‘the insolence of office’. Perhaps you are one of the thousands of people who have been pulled over by a man in uniform for ‘speeding’ in an area where the speed limit is set arbitrarily low, when it is patently obvious that the only function of the speeding ticket is to raise revenue? If you are an employer, are you happy that you’re obliged to act as an involuntary unpaid tax collector, removing large chunks of your employees’ wages for remittance to the Tax Office and being forced to bear the costs in time and money of this collection and remittance?

What makes these encounters unpleasant in a way that your dealings with commercial bodies are normally not unpleasant is that, as Jan Narveson puts it, ‘agents of government have a relation to you that nobody else normally has.’ If you get poor service in a restaurant, you can protest. If you’re mobile phone refuses to function, you can take it back to the store and demand an exchange or get your money back. But if you don’t like what you are made to go through at an airport, don’t even think of protesting and if you think you pay too much in tax, just what do you propose to do about it? ‘Government,’ as Narveson says, ‘can “do bad things to you” and they can make it stick….The law, literally, is on their side: They claim, indeed, to be “the law.” If you disagree – well, too bad for you!’ [6]

read on...

No comments:

Post a Comment